Recently across our state, there have been efforts to remove lead connectors and lead pipes from houses and water systems. Now, the dangers of lead pipes are well known. But nearly 145 years ago, Professor Robert Kedzie warned of the dangers of lead products, but was ignored. On this episode, we spoke with the Michigan History Center’s Rachel Clark to learn more about Robert Kedzie and his groundbreaking research.

In the 1800’s lead was used for cookware, things like plates and kitchen utensils. However, there were people in the 1800's that thought lead products could be dangerous including Robert Kedzie, a chemistry professor at Michigan Agricultural College, now known as Michigan State University.

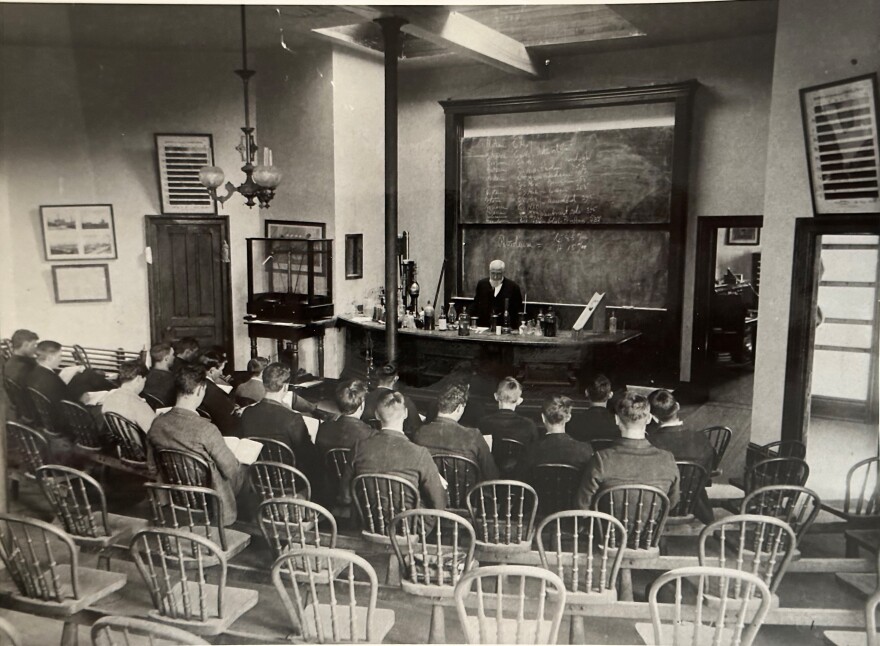

Robert Kedzie was born in New York in 1823 and moved with his family to Lenawee county at age 3. He earned his medical degree at the University of Michigan in 1851. When the Civil War broke out, Kedzie enlisted as surgeon and was a POW, he was later released due to health issues in 1863. When Kedzie returned home he became a chemistry professor at Michigan Agricultural College and remained as a professor until his death in 1902. During his tenure, Kedzie was very active in Michigan’s political and medical professional community.

“[Kedzie] also was in the Michigan House of Representatives in 1867, Michigan Medical Society, 1871, Michigan Board of Health in the late 1870s into 81. And his specialty…a lot of the time was food and household safety,” Clark said.

Lead poisoning started to become an issue a few centuries ago. Doctors were writing letters because they were concerned about symptoms of lead poisoning in their patients. They traced the root cause of the poisoning to cookware products that were lined with lead. Back then, manufacturers were making cookware products with tin and mixing the tin with lead. Over time, the cookware products would wear down and the lead would begin to degrade and seep into food and water. Kedzie saw the issue and realized that lead poisoning takes some time to take effect.

“ So [Kedzie] sounded the alarm in the late 1870’s about the dangers of lead poisoning and especially in what they're seeing in children. But as we know now, lead poisoning is a long game. It's rare that you see an acute poisoning from everyday use. It's these long term exposures. And that's what he was actually warning everybody about,” Clark said.

When Kedzie discovered the issue, he gave an address to the Michigan Board of Health warning them about the dangers of commercial products that were made with lead. Back then, lead wasn’t just used in cookware, it was used in roofing materials, paint and pipes. The Board of Health acknowledged his work but because of the widespread use of lead products and having no real authority, nothing was recalled or changed.

In 1978, the United States Congress finally passed a ban on lead paint, nearly a century after Kedzie's research. It took Congress a long time to come to an understanding of the dangers of lead for a variety of reasons. The medical community did not always recognize lead poisoning in patients, there may have been other reasons patients were getting sick. Also, companies that manufactured products with lead didn’t want to stop using lead in their products.

“There are letters from 1900 from a very popular paint company that acknowledged they knew the dangers of lead in their paint, but they didn't change anything because they were making money.” Clark said.

The response that Kedzie received was frustrating to him. Kedzie brought in all the evidence he could but in the end, the Michigan Board of Health didn’t have much decision-making power.

“He was very adamant about safety standards in household goods. He had written reports about household oils in lamps, the lead poisoning or the lead concerns were part of that. And he brought in letters. He brought in other doctors. He brought in as much evidence as he could to try to convince that Board of Health to do something. But at that time, the Board of Health in Michigan, it didn't really have any power. It was just a board. But it really it's not like today where there is power behind the Department of Health. And so he was very frustrated,” Clark said