To make sense of the present, it sometimes helps to look to the past. One moment in history that’s particularly relevant to our current moment is the tuberculosis epidemic during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Despite the differences in daily life and the advances in medicine and technology since then, the country’s response to tuberculosis outbreaks has clear parallels to the current COVID-19 crisis.

Both COVID-19 and tuberculosis can be transmitted via airborne droplets, which means the public health messaging for both diseases have a lot in common.

“The things that we hear today with COVID are very similar to what the [Michigan] Board of Health was putting out back in the 1880’s and 1890’s,” said Rachel Clark from the Michigan History Center

Of course, there were some important differences, too.

“They had lots of pamphlets and information pieces about spitting in public, which today is disgusting to think about, but a lot of people chewed tobacco back then, so spitting in public was very common.”

Clark says that the Michigan Board of Health relied on these pamphlets because there was little else they could do to stop the spread of the disease. But these informational campaigns were not very successful, according to Clark. The pamphlets were printed in English, which meant they were most useful for upper-class, literate, English speakers.

“The print campaigns were successful to, I think, the audience [that] could read it and understand it, but they were very very limited in terms of the people who were truly suffering from tuberculosis,” Clark explained. “Which are going to be your poor, lower [class], immigrant populations that are crowded into cities, not only in Michigan, but throughout the states.”

Funding was also unequally distributed to different populations across the state. For example, says Clark, the city of Detroit caught flack for not allocating resources to the populations that were most in need, which helped fuel inequity in health outcomes, Clark said. That trend, she added, continued well into the 20th century.

“When there is a plague and there is a pandemic or any major health crisis, there is a group that is blamed, and it’s typically a group that is othered in some way—whether it is an immigrant group or a religious minority. And a lot of times the reason they are considered part of a problem is, as I said, the information that is put out to help the population is not translated to any of those people,” Clark said. “So it is easy to other them, and to set them aside, and blame them for the spread in their own neighborhoods and in their own communities.”

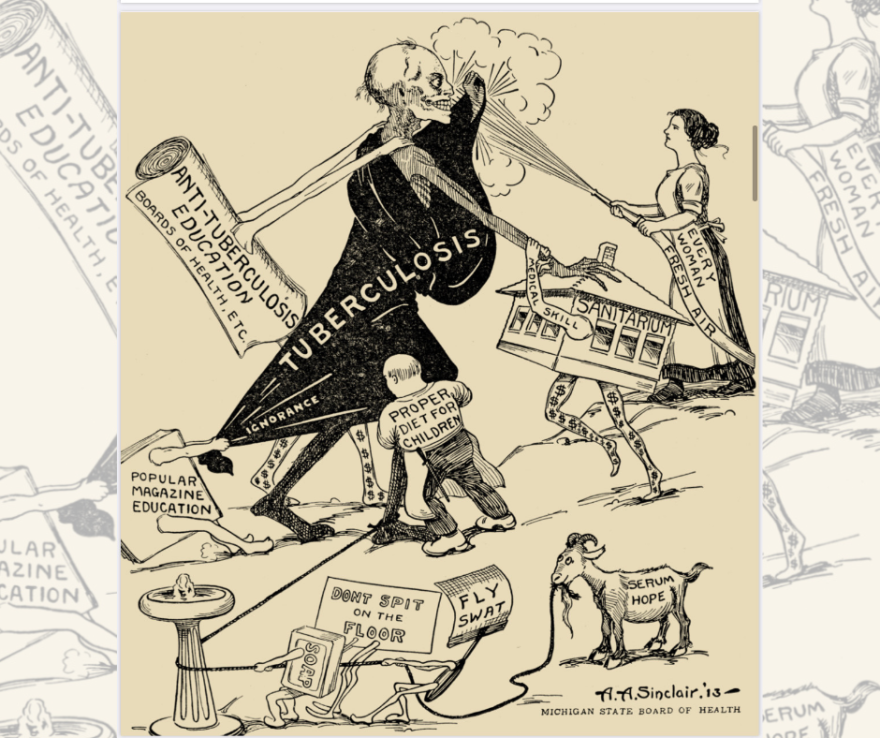

Starting in the 1910s, people began to realize that tuberculosis wasn’t connected to any particular race or class. Public health materials became more acessible and spread via schools and political cartoons. Clark says that this created a sense of “camaraderie” and resulted in a more concerted effort to fight the disease.

This article was written by Stateside production assistant Olive Scott.