This story is part of Michigan Public's series "Mornings in Michigan," which features morning moments from across the state.

At least 25 million American adults suffer from sleep apnea, according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

Julie Gibb is one them.

Gibb, 47, is a mother of four. She's upbeat and active. She just can't get a good night's rest.

Checking in

We met up with Gibb as checked in for the night at a Michigan Medicine sleep clinic in Ann Arbor on a weeknight in September.

“I brought my journal. I got a book because I try not to use my phone a lot at night, you know, the things that we're all trying to get better at,” Gibb said with a laugh.

“I took the things that were helpful for me to be successful that I normally do at home, like a nice pair of pajamas, something to wash my face, those kind of things.”

For a long time, Gibb has suspected this night would come, but she wasn't exactly looking forward to it.

“I also have a family history of sleep apnea. Both of my parents were diagnosed with it. And so I was hoping that I'd skip that part of my genetics,” Gibb said.

Gibb allowed three Michigan Public journalists to observe her stay at the clinic. She’d been experiencing the most common symptoms of sleep apnea, which causes people's breathing to pause frequently while they're asleep.

“I was waking up multiple times a night and not getting any restful sleep. And that's hard to do when you're functioning with raising children,” she said.

Inside the control room

The clinic is one of four run by Michigan Medicine with a combined total of 38 beds. They see adults and children. The night of our visit, there were 11 patients at the clinic. Gibb had her own room — one bed, a chair, a TV on the wall, and a bathroom.

Across the hall, clinic supervisor Mark Kingen gave us a tour of the control room where seven technicians were getting ready to work all night to monitor the patients. There are cameras in the bedrooms and the technicians can hear patients when they speak out.

“Techs can tell if they're asleep or awake. Kind of like Santa Claus,” Kingen said.

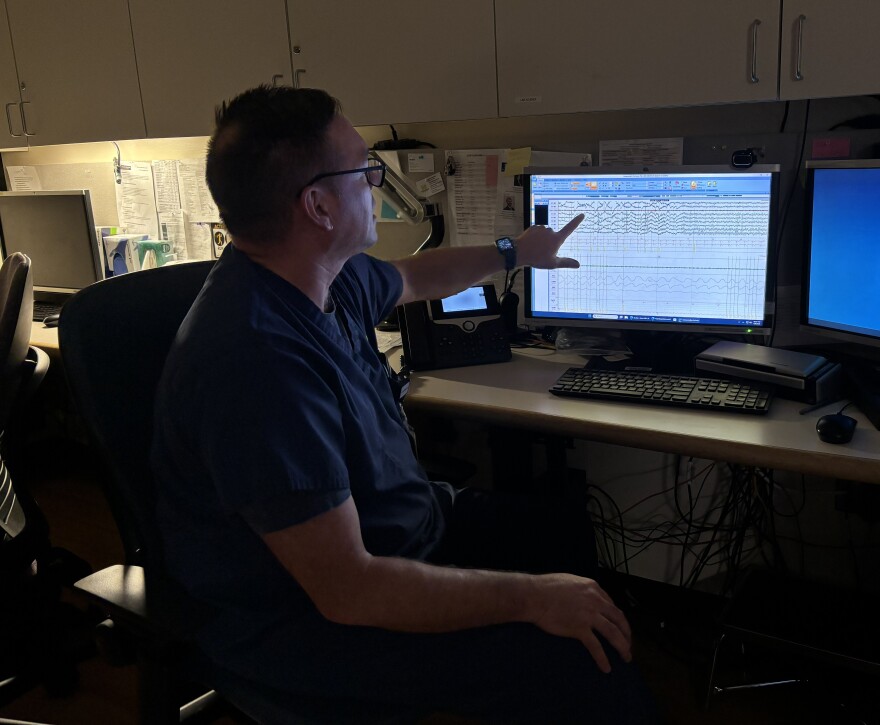

He called up a sample study on a computer. The screen filled with about two dozen rows of squiggly lines in different colors. Each long waveform represented something the technicians are tracking.

"We're watching the brain waves. We're monitoring eye movements and muscle tone. We're monitoring air flow, limb movements, their muscles in their legs, their heart," Kingen said, giving us a partial list.

Wired up

To collect all of that data, you need wires. Lots of wires.

Jasmine Murdock was the sleep technician assigned to monitor Gibb. Behind Gibb's bed, dozens of thin wires with diodes at the ends extended from a panel on the wall. Murdock started attaching them to Gibb. Earlier in the evening, Gibb had mentioned she styled her hair for our interview, but Murdock attached wires in it, messing with her blond curls.

Murdock walked her through the purpose of each contact point.

"I'm going to do the ones on your chin. Those will let us know if you grind your teeth at night,” she said.

In all, Murdock taped about 30 diodes to Gibb's head, neck, chest and legs. The wires were all different colors to make it easier for the techs to identify if they fall off in the night. They trailed out behind Gibb's head and neck.

"You just look like a robot unicorn with a beautiful unicorn mane," Murdock said.

"Oh. You're sweet. I've never been called a unicorn before," Gibb said, laughing.

"That's what I tell the kids," Murdock said.

The mask

Gibb already knows she has sleep apnea after taking a home test, which has become a common first step prescribed by doctors. What she's here for tonight is called a titration. She’s being fitted for a mask to connect to a continuous positive airway pressure — or CPAP — machine.

Even though her parents, two of her kids, and even her husband already had CPAP machines, Gibb put it off for as long as she could.

“I've been making jokes about, I don't want to be a Snuffleupagus because I don't want to have this thing attached to me at night,” she said, referring to the hose that connects to CPAP masks.

After trying on four types of masks, Murdock and Gibb settled on one. For the titration, Murdock adjusted the air pressure flowing through the mask during the night, until they found the right setting.

As patients get ready for bed, the clinic wants them to try to follow their normal routine, so they get to sleep more easily. Gibb ducked into the bathroom to brush her teeth and we followed Murdock out of the room and back across the hall to the control room.

Tired of being tired ... or maybe not

That's where we met Rachel Ford, who is the clinic’s lead technician and serves as a coordinator.

”Some people are really tired of being tired and are ready for anything that's going to make them feel better," Ford said.

But she says most people don’t want to be here.

"I think a lot of people — their doctors will send them in because other issues are going on and they think they sleep fine, and you watch them at night and just go, I cannot believe anyone sleeps [so poorly] and then functions," Ford said.

"Like, you're going to drive home after a terrible night of sleep? And people think they sleep great. It's crazy. But they've been sleeping bad for a long time. They're just kind of used to it.”

In the control room, Murdock sat down at a desk where she could hear Gibb and talk to her through a mic. She walked Gibb through a few movements to be sure her computer is picking up the signals from all those wires and diodes.

When Gibb drifted off, it was time for the sleep-deprived Michigan Public journalists to head home for a few hours of sleep of their own.

An early wakeup call

We returned to clinic the next morning and were in the control room at 5 o'clock. Murdock told us she had to go into Gibb's room overnight to add a chin strap to the mask — a sort of ace bandage around her jaw — to keep her mouth closed to help her get the most air.

And then it was time for Gibb's wake-up call. Murdock buzzed in from the control room.

“Good morning. Julie, your sleep study is all over. I'm gonna have you lay on your back, and we're going to do those exercises we did last night, okay?”

A few minutes later, we headed back into Gibb's room and talked with her as Murdock turned off the CPAP machine and removed the diodes. When we asked how she slept, Gibb gestured to the chin strap wrapped around her head.

"Well, obviously, I opened my mouth," she said.

After the overnight adjustments and increase in air pressure, Gibb told us she slept more deeply than she had in weeks.

"I could tell the difference already. I really have not been breathing well."

Disconnected from the wires and somewhat rested, all Gibb had left to do was take a shower to wash off the adhesive for the diodes and fill out a questionnaire. Then she headed home.

CPAP at home

After her stay, it took about six weeks before Gibb got her own CPAP machine. After she did, we caught up by Zoom. She had been using the machine for a little less than a week.

"It’s an adjustment," she said. "It takes some time, but I can already tell a difference in my sleep quality."

She noticed a difference in her energy, too.

“Absolutely different. Energy has improved. Ability to think better. I actually remembered a whole list of things the other day, which I haven’t for a long time. So those are improvements.”

When we spoke, Julie Gibb also came back to the reason she agreed to let us shadow her entire sleep study. She wants other people to get help, too.

“I would just say if your sleep quality is not great, talk to your doctor about it. That's why I did this. I mean, this is not easy to be vulnerable in this big way when you're going through something like this, but I really hope that people will take it seriously because it really could mean a difference in your quality of life. That’s how serious it is to sleep and breathe.”