The sandy shore at Oval Beach in Saugatuck is dotted with beach chairs and flip flops when a small group of scientists unloads from the van wearing long sleeves and pants with the socks pulled up over the cuffs, to keep the ticks out.

“Our mission today is we’re investigating the source of these high nitrate concentrations in well 10,” Suzanne DeVries-Zimmerman said, holding a clipboard full of papers.

DeVries-Zimmerman is a professor of geology and she’s here with a fellow geologist and two student researchers. They are part of the Dune Research Group at Hope College.

Scientists estimate the dunes of West Michigan formed mostly between 3,500 and 5,000 years ago.

“I have more than a few friends that are convinced this whole beach dune research is a total scam, and nothing but an excuse to go to the beach,” DeVries-Zimmerman said.

It’s hard not to be jealous of this unique research group, whose scientists get to study this unique ecology. The dunes along the western edge of Lake Michigan are a relatively young feature of the landscape. The sand dunes formed, scientists estimate, mostly between 3,500 and 5,000 years ago, after the glaciers retreated. Wind and waves pushed the sand ashore, forming the massive dunes. Their size has fluctuated over time, but the overall scale is relatively stable. They are the largest dunes on any freshwater coast in the world.

The research group at Hope College has been studying these dunes within an area north of Oval Beach for more than a decade, as water levels on Lake Michigan reached record lows in the early 2010s and then record highs at the start of this decade.

DeVries-Zimmerman’s particular interest is in the wetlands nestled between the towering mounds of sand. These interdunal wetlands were drenched when water levels on the lakes went up.

“And all these species just popped out of nowhere from the seed bank,” DeVries-Zimmerman said. “It was absolutely fascinating to watch. I mean these seeds literally sat around for 30 years waiting for water.”

That water has now receded and a new cycle is underway in the dunes. Along the shore, DeVries-Zimmerman and her colleague Brian Bodenbender point out areas along Oval Beach where the beach grass - they call it marram grass - is growing back, allowing sand to pile up in small mounds.

DeVries-Zimmerman said when these “shadow dunes” start to connect, they form an “embryo dune.” Eventually these connect and become the new foredunes, the low shelf of sand covered in grass near the shore.

The mystery in the groundwater

But on this particular day, DeVries-Zimmerman and her group are not focused on what’s happening onshore.

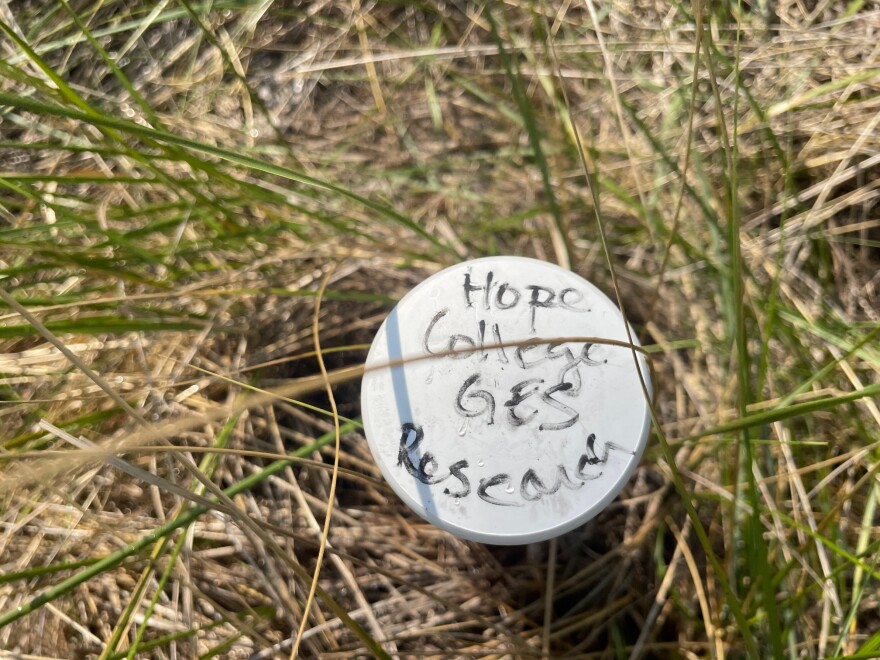

Instead, we head over the first ridge of dunes to a small pond, where the student researchers, Caitlyn Brown and Carter Dean, duct tape a plastic bottle to the end of a stick to collect a water sample. They’re collecting samples to test a hypothesis about nitrates in the water.

These dunes sit near the mouth of the Kalamazoo River, and the wetlands are between the river and the Lake Michigan shore. At one of their sample wells on the river side, they’ve noticed high levels of nitrate – which is thought to come from fertilizers running off of farms. Nitrate levels have been lower in wells closer to the Lake Michigan side.

“What we need today is to confirm the river is the source of the nitrate that we’re seeing in that well,” DeVries-Zimmerman explains.

The hypothesis here is that these interdunal wetlands are helping capture some of that harmful nitrogen runoff from farms, and keep it from going into Lake Michigan.

To prove it, they need more samples. So off we go, following narrow, unmarked paths through the tall marram grass, stopping frequently to check for ticks on pant legs and backpacks. As each new tick is plucked off, they place them in small, clear vials of ethanol. Each person carries their own vial, their own pocket collection of ticks.

Not on a proper oceanic coast

Bugs aside, a hike through the dunes is not a bad way to spend a work day. For Devries-Zimmerman, it’s the fulfillment of a childhood dream and a way to stay connected to this magical place.

“We’ve had colleagues from our sister institution Liverpool Hope, and other institutions within the (United Kingdom) come to visit,” she said, “and they’re always taken aback by the size of our parabolic dunes here on this freshwater body. One colleague said when he saw them, he said ‘I thought I was going to weep.’”

There are a small number of researchers worldwide who study dunes. Smaller still is the group that specializes in freshwater dunes.

I asked DeVries-Zimmerman and Bodenbender how strong their feeling of superiority was over colleagues who focus on oceanic dune systems.

“Not very strong actually,” Bodenbender admits.

Their work, the research on the largest dune system on a freshwater coast anywhere in the world, has been called “parochial,” DeVries-Zimmerman said.

“Because they don’t consider our dunes coastal dunes because we’re not on a proper oceanic coast,” DeVries-Zimmerman said.

And yet, they carry on.

After tromping through deep grass, pulling off ticks, Carter Dean and Caitlyn Brown, the student researchers, collect the samples from the Kalamazoo River.

Back in the lab, today’s samples will be compared to the other samples in the wells inside the interdunal wetlands.

And the following week, DeVries-Zimmerman texted me the results. Nitrate levels were not higher in the river, as expected.

Their hypothesis was shot. Nitrate levels remain high in the well near the Kalamazoo River, but the river is not the source of the nitrate, at least, not based on these results.

The mysteries hidden in the dunes prevail. So the research continues.