For years, Chris Dorch watched others around him in prison be released from sentences that were supposed to keep them behind bars for life.

“It was a moment where I felt very happy for them,” he said.

Dorch was convicted of first degree murder for shooting and killing a man when he was 18. Michigan law requires a mandatory life sentence without parole, the harshest punishment the state allows.

“I knew a lot of these young guys… without excusing what it is that we did, without minimizing what it is that the families went through or suffered because of what it is that we did, I understood there was more to the story than just the act itself,” Dorch explained.

In 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled states must reconsider mandatory life without parole sentences for people who were younger than 18 when the crime was committed. The court ruled such sentences are “cruel and unusual,” citing scientific evidence that suggests adolescent brains aren’t fully developed.

Since then, Michigan courts and lawyers have been slowly working through hundreds of resentencing hearings for the more than 370 juveniles convicted of murder.

“I could see a glimmer of hope in terms of them doing something for individuals that were my age because we were impacted by the same set of brain dynamics that they were impacted by,” Dorch said.

That hope proved justified.

A series of Michigan Supreme Court rulings struck down mandatory life sentences for 18 year olds, and then extended the same protection to those who were 19 and 20. Over 750 people are now eligible for resentencing under these rulings, according to data Michigan Public obtained and analyzed from the Michigan Department of Corrections.

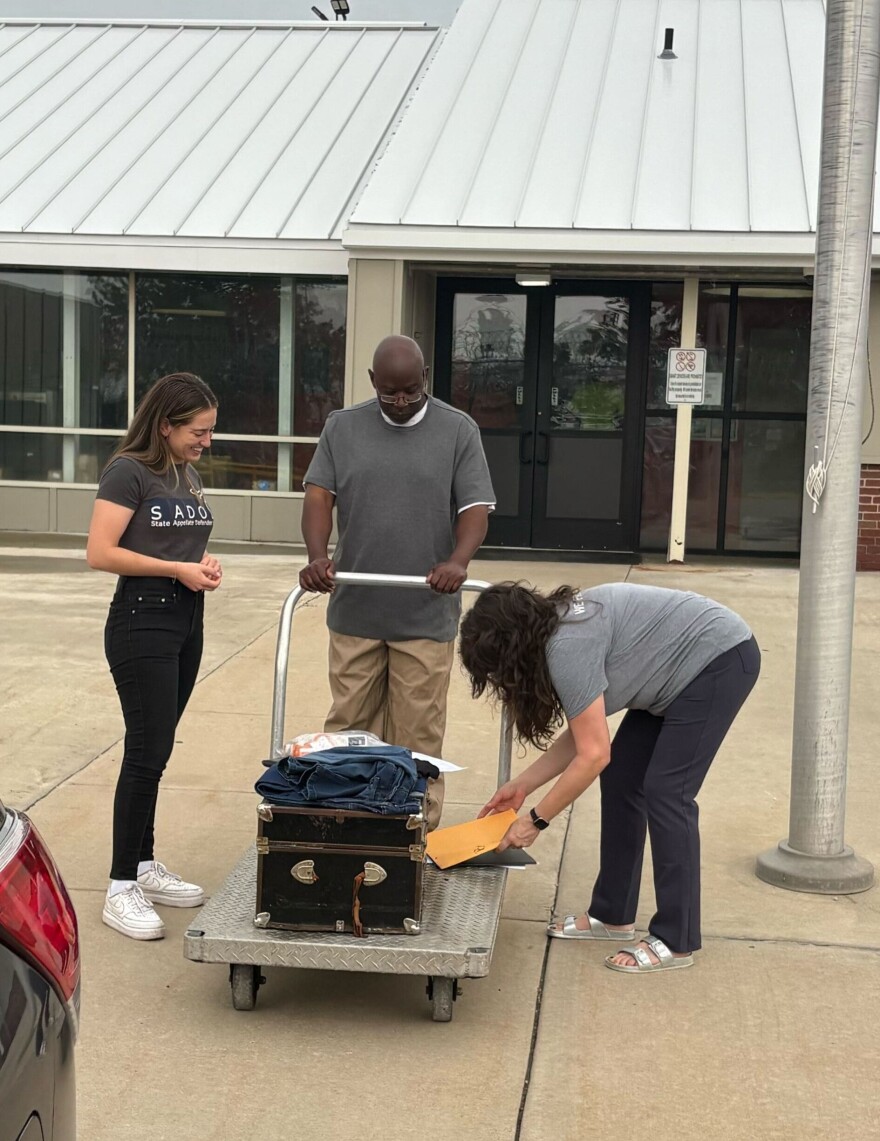

Dorch is now free and living with his family in Oak Park.

“It still doesn't feel like it's happening,” Dorch said of his newfound freedom after over 32 years in prison. “I'm still doing the time right now. Much like the [victim’s] family is, there's no end to their suffering. And I don't put myself on par with them because the suffering that they deal with is different. I suffer with a guilt and a shame for what I did.”

Pushback from prosecutors

The decisions have sparked both hope and concern across the state.

J. Dee Brooks, Midland County prosecutor and president of the state prosecutor’s association, said his members understood the rationale when it applied to juvenile defendants under age 18.

But extending the same protections to 18, 19, and 20 year olds, he argued, goes too far.

“I think it's quite frankly, a gross overgeneralization, to say that every 18 and 19 and 20 year old brain is not developed fully or sufficiently for them to be held fully accountable for an act of first degree premeditated murder,” Brooks said.

Under the new rulings, judges still have the option to impose life without parole, but on a case-by-case basis.

“There are some people who will argue that first degree murder, regardless of age, shouldn't be a mandatory life without parole. That (sentences) should be up to the sentencing judge … And I get those arguments,” Brooks said. “But that should be up to lawmakers, not the courts.”

Brooks also raised concerns about resources, noting prosecutors face a deadline to decide if they want to reimpose a life without parole sentence.

"Some places like Wayne County, where they have almost 400 of these cases, that's pretty much an impossible task,” he said.

Loading...

Even in counties with lighter caseloads, prosecutors said they’re struggling to keep up with the influx of new cases these rulings bring. In May, Genesee County prosecutor David Leyton told Michigan Public his office is still struggling to finish resentencing hearings for the 17 and under group.

“When I went to my board of commissioners recently, I told them, ‘look, I need help.’ I need more staff. I need more lawyers. I need more paralegals. I need more victim advocates. I need more support staff,” he said. “And I don't just need it for a short time. It has to be sustained, sustainable funding because this is going to go on for 10-15 years.”

The Michigan State Appellate Defender Office expects prosecutors to decide if they’ll seek life without parole again for the cohort of 18 year olds by December 29, 2025 and January 5, 2026 for the group of 19 and 20 year olds.

“Prosecutors are awaiting additional clarity on the final deadlines,” Brooks said.

Chris Dorch was able to go free relatively early. He’s one of a few dozen individuals who were let out of prison or got a lighter sentence ahead of the Supreme Court’s timeline because prosecutors chose to allow it or because of appeals court rulings.

“If it feels like there's a lot of people to be resentenced, it's because there were a lot of people that were unconstitutionally sentenced in the first place,” said Marilena David, director of the Michigan State Appellate Defender Office.

Offering the defendants a second look “will show that they do have the greater potential for rehabilitation that entitles them to a review of what their sentence should be,” she said.

David acknowledges that reopening cases can be painful for victims’ families.

“We have to get it right the first time, and we have to follow the law, and we have to make sure our laws are constitutional, that the sentences we impose are individualized and constitutional, so that we don't have to ask victims’ families to go through this again.”

Loading...

Resentencing is far from a guarantee of freedom. The minimum sentence is still 25 years. Based on that, a Michigan Public analysis found that about 21% of the individuals affected by the state Supreme Court rulings will not be eligible for release until at least 2035.

Even after serving their minimum sentence, individuals will have to get approval from a parole board to go free.

At least 60% of the people who are now eligible for resentencing under the state Supreme Court rulings are already 50 or older, according to Michigan Public’s analysis.

“I thought we had justice until this happened.”

For some, the rulings have reopened old wounds.

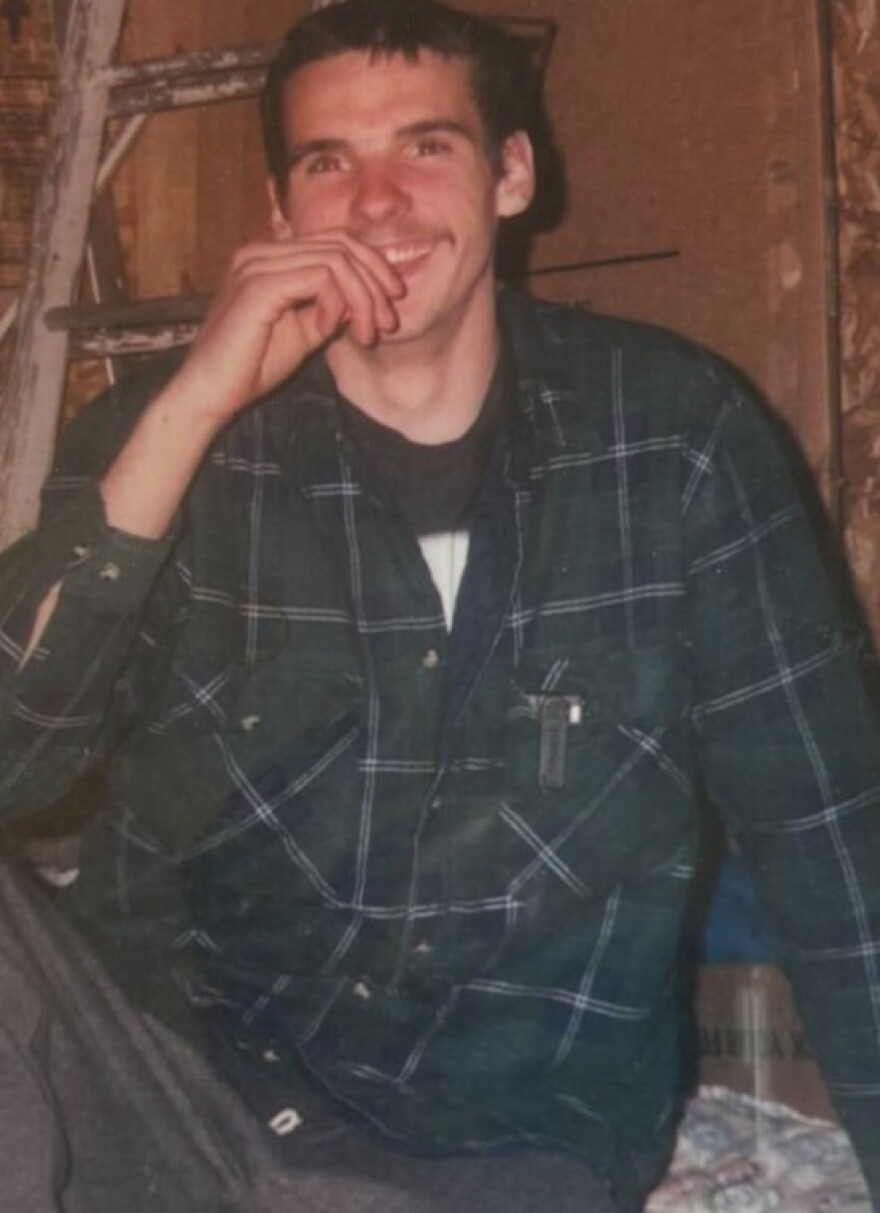

Jennifer Cline’s brother, Joseph Knope, was killed nearly 30 years ago in Wyandotte when he was 19.

"Joe was something special,” she recalled. She said her big brother was protective; that he had a form for any of her potential boyfriends to fill out before they could go on a date.

"Joe was the kind of human being who would help a random stranger or pick up someone on the side of the road," Cline said.

The person who killed Joe was also 19. Now, he will have a chance at resentencing.

“I thought that we had justice, and I would never have to see this guy ever again. And that he was in prison and would never hurt anyone ever again," Cline said. "I thought that we had justice until this happened."

She said she’s never seen her brother’s killer, Jason Mourguet, show remorse. She does not believe he deserves the chance to go free simply because of his age.

“19 year olds are old enough to make life choices. 19 and 20 year olds are old enough to make big decisions and close on houses and go into the military,” she said. “And so why wouldn't they be old enough to make a decision like he made?”

Cline said she would be “petrified” for herself and her family if Mourguet were released.

"The fact that this is even on the table blows my mind," she said.

Living with both freedom and guilt

Chris Dorch, who spent more than 30 years in prison before his release this summer, said people like Cline are justified in their anger and resentment.

“You're right. We do not deserve it. If it's a matter of what we deserve, then I’d still be in prison rotting,” he said.

Dorch doesn’t argue that his age excuses his crimes.

“I didn't take any consideration for, or I didn't take any, any noticeable consideration for the suffering that I had caused to the family,” he said. “I didn't acknowledge their pain when I was going through sentencing or when I was going through trial.”

Since then, Dorch said he has come to understand that it’s not just “about Chris.” He said he had to learn to feel empathy and take responsibility for the hurt he caused to people around him and the victim.

“I can't even ask that you empathize with me, but I will ask that you share with me in understanding that change comes because an individual sees himself and takes a position against himself for the wrong that he's done,” he said.

“And that individual is no longer the individual that you knew. He's someone completely different.”